The lockout-shortened 1999 season was the worst in NBA history. It was the shortest, the ugliest, and, at least until recently, the all-around weirdest. For the NBA, it was rock bottom.

In 1995, following a brief work stoppage, a six-year collective bargaining agreement was reached between NBA players and NBA owners. In 1998, the owners exercised a clause in the agreement which allowed the CBA to be re-opened based on player salaries drawing more than 51.8 percent of total basketball-related income. The owners wanted to implement restrictions on how much players could be paid, as prior to the lockout, due to salary-cap loopholes, their was essentially no limit to what teams could pay to re-sign their own players. It’s widely assumed that Kevin Garnett’s record-breaking $126 million contract, which he’d inked with the Timberwolves in 1997, was the driving force behind the owners’ drastic leap to action.

The lockout lasted 204 days, from July 1st, 1998 until January 20th, 1999. Commissioner David Stern, already considering the radical idea of replacement players for 1999-00, announced that he would cancel the season if no deal was reached by January 7th. On January 6th, in an eleventh-hour meeting in New York, the two sides finally came to an agreement. The owners mostly got their way, with player salaries being capped at $14 million for players with ten or more years’ experience, $11 million for players with six to nine years, and $9 million for players with one to five years. Additionally, the rookie pay scale was put into place, and drug testing was expanded to include marijuana and PEDs.

The lockout was viewed as a bad look for both sides, but especially for the owners, who were perceived as utilizing their substantial advantage in leverage to force their employees into a settlement. In all, three full months and 464 regular-season games were lost to the lockout. It was the first time in NBA history that games were cancelled due to a labor dispute. The 1999 All-Star Game was cancelled, and NBA ticket sales and TV ratings declined sharply. A 50-game schedule was hastily put together and slated to begin on February 5th.

One week after the agreement was reached, Michael Jordan announced his retirement from basketball. The Bulls, who had been in a state of limbo awaiting Jordan’s decision, then traded Scottie Pippen to Houston for Roy Rogers and a second-round pick, and released Dennis Rodman on January 21st, just prior to the commencement of the truncated season. Phil Jackson had stepped down immediately following the 1998 Finals, and Tim Floyd was hired as Chicago’s head coach. The Bulls fell apart, going 13-37 for the season, their first of six straight losing campaigns. It was an undignified death to one of the NBA’s greatest dynasties.

In addition to the unsavory optics of the owners strong-arming their players, the hundreds of lost games, the cancellation of All-Star Weekend, and basketball’s greatest player retiring in the immediate wake of the fiasco, 1999 was a singularly ugly season in terms of on-court product, as well. The league’s overall scoring average of 91.6 was the lowest since the introduction of the shot clock in 1954, and the NBA’s collective field goal and free-throw percentages of .437 and .728, respectively, were the worst since the mid-sixties. Allen Iverson’s lockout-season scoring average of 26.8 remains the lowest of the shot-clock era for a league leader, and just one team, the Sacramento Kings, averaged more than 100 points per game. For perspective, in 2018-19, no team averaged LESS than 100 points per game.

35-year-old Karl Malone was the MVP of the 1999 season. It was his second MVP award in three years, and the fact that he won it averaging a relatively pedestrian 23 and nine speaks to the state of the NBA game at that time. That being said, what the Mailman was able to accomplish at nearly 36 years old was in fact quite remarkable: he played in 49 of 50 games and led the ancient Jazz to a tied-for-NBA-best record of 37-13. Still, he was the least exciting possible choice for the NBA’s most prestigious award, and his selection added to an already bizarre collection of accolades which included Antonio McDyess making an All-NBA team and Darrell Armstrong(!) winning both the Sixth Man of the Year and Most Improved Player awards.

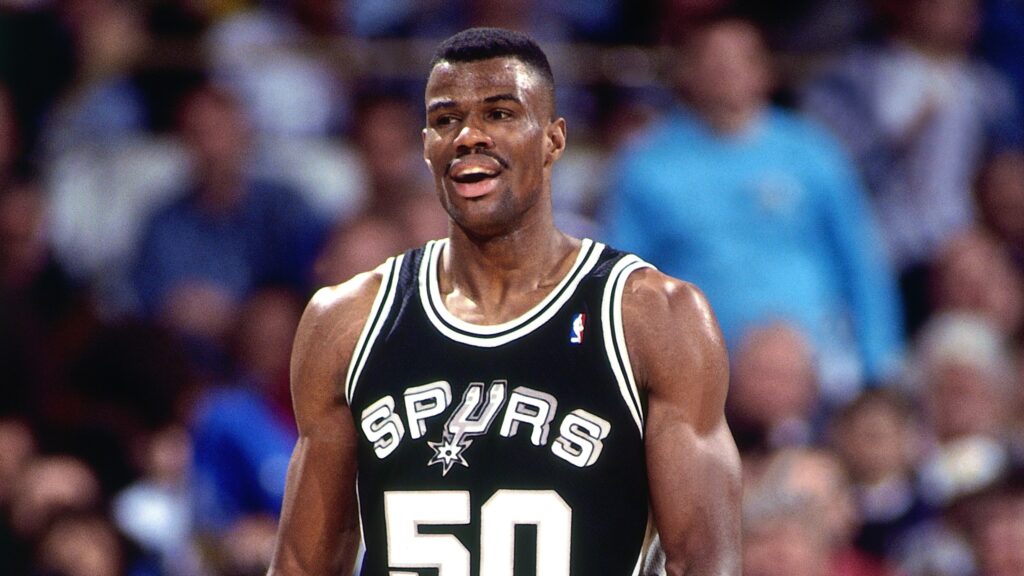

The 1999 NBA Finals pitted the Spurs against the Knicks. It garnered the lowest television ratings of any Finals in seventeen years and stifled a five-year uptrend, falling nearly 40 percent from the previous season. The Knicks, without Patrick Ewing, who had torn his achilles in the Conference Finals, were led by Allan Houston and Latrell Sprewell, and became the first and only number eight seed to appear in the NBA Finals. The top-seeded Spurs were led by Tim Duncan and David Robinson, and they steamrolled the Knicks in five games. It was as unsightly a championship series as the NBA has seen, with neither team reaching 100 points in any game, an ignominious and subsequently unequaled feat.

If there was one bright spot to be found within the 1999 season, it was a stellar rookie class which featured Vince Carter, Paul Pierce, Jason Williams, Mike Bibby and Dirk Nowitzki. Unbelievably, Nowitzki, who retired sixth on the NBA’s all-time scoring list, was omitted from both the All-Rookie First Team and the All-Rookie Second Team, as he was deemed less deserving than such basketball luminaries as Matt Harpring, Michael Doleac and Michael Dickerson. Vince Carter was named Rookie of the Year after averaging 18.3 points per game and electrifying, with his awe-inspiring dunks, an otherwise regrettable NBA season.

The NBA’s popularity suffered immensely due to the lockout, with television ratings and ticket sales declining steadily over the ensuing three seasons. For the next half-decade the league existed in a state of diminished health unimaginable in the thriving NBA of the present. It wasn’t until the arrival of LeBron James and the 2003 draft class that an upswing began to take place.

In 2011, a labor dispute caused the NBA to come to a halt once again, this time shortening the season to 66 games; but the lessons gleaned from the disastrous 1998-99 work stoppage enabled the league to emerge from its second major lockout relatively unscathed. Now, with the NBA on indefinite hold, one can’t help but wonder if and how the league’s experience with shortened seasons will be applied in these coming months. Entirely different and utterly sinister forces are at work, so beyond the possibility (likelihood) of truncation, the two situations cannot in fairness be compared. Still, and despite the obvious reality that these globe-spanning forces are beyond the control of the NBA and its players, precedent-setting, history-altering decisions will soon have to be made.

We are, all of us, entering a new world which will entail new ways of life; and what the league learns from this unforeseen and still-unfolding disruption will dictate the manner in which similar circumstances are anticipated, navigated, mitigated, and resolved in the future. Much like the lockout-shortened 1999 season, 2019-20 has been, albeit for very different reasons, incomparably bizarre; and just like 1999 it will, in retrospect from relative normalcy, prove a landmark of historical significance.